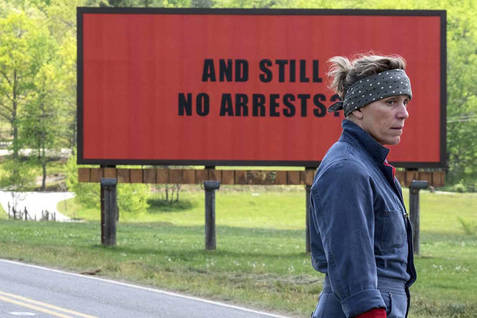

B+ | An enraged and grieving mother harangues the police department to find her daughter's murderer. Directed by Martin McDonagh Starring Frances McDormand, Sam Rockwell, and Woody Harrelson Initial Review by Jon Kissel |

Martin McDonagh’s three films have all had playful tones that dare to butt up against truly ugly plot points. In Bruges begins with the murder of a child while Three Billboards is shot through with grief and regret. Even Seven Psychopaths, his most frivolous film, contained surprising moments of pathos. Amongst varying amounts of blackness are characters that remain handy with a joke or acerbic retort or a withering monologue, which keeps things from ever getting unbearable. This is especially true in Three Billboards, which often contains breakneck changes in tone. While this is usually a crutch and an inconsistency, it feels earned here. Characters can be engaging in caustic and witty repartee before things take a sharp turn into something different, where cutting words are replaced by blunt instruments. An argument can become an understanding, or a violent outburst, and sometimes both. The principals are soaked in conflict, inducing a state of preparedness that never lets them fully take their masks off.

What kind of masks the characters are wearing makes Three Billboards more unique than a standard revenge movie. Mildred is shown to be someone for whom this is not her default mode of existence, standing ramrod straight with a bandanna and cajoling the town into caring about her daughter’s killers. For 98% of Three Billboards, she wears that persona but there are vital moments when we see the warmer individual underneath. It’s in those moments that McDormand won her Oscar, because they are perfectly incongruous with who Mildred is in anger and perfectly genuine as well, and one of Three Billboards’ many tragedies is that the better version of Mildred is likely to never fully assert itself over the meaner one. Dixon’s mask is more easily seen through. His is that of a competent police officer deserving of the job, but his every action marks him as the opposite. His uniform grants him the benefit of the doubt from people who would otherwise accurately judge as a malformed brute. Cruel and stupid, Dixon feels like a sadly real archetype, the buffoon who cloaks his insecurity in raw power, or more accurately, is allowed to cloak himself by those who should know better. Willoughby is also wearing the mask of a protector of the peace, but his employment of people like Dixon put the lie to that. All the adulation of the town is cold comfort to unsatisfied victims like Mildred, to say nothing of the individuals that Dixon never denies abusing.

This is where Three Billboards falls down from a heretofore considerable height. McDonagh raises the specter of racialized police violence but never makes it more than a character detail for the perpetrator of said violence instead of the victim of it, who is never shown or even named. It’s believable that such a thing would happen, and it’s believable that a secluded town like Ebbing would be able to avoid the widespread opprobrium such abuses now bring, but McDonagh seriously errs by making it such an irrelevant event. Dixon also like to wear cargo shorts, a detail as relevant to his character as his racist abuse. McDonagh compounds this underlying flaw by giving Mildred a black best friend, Denise (Amanda Warren), straight out of They Came Together. Denise has no inner life and only lives to support Mildred, up to and including after she’s unjustly arrested by Dixon, spends several days in jail, and upon release, is primarily concerned with how Mildred’s doing. The form of Three Billboards is such that characters are more vessels for ideas than full individuals, a fine approach that is devalued by how badly McDonagh treats Denise and Dixon’s first victim.

The inclusion of racialized violence might be present due to that being a particularly enraging issue in present society, and McDonagh wants to add as much to the rage quotient as he can. The police are the primary focus of that rage, though the film treats their response to violence against woman far more seriously than Dixon’s brand. Mildred’s ex-husband, played by John Hawkes, is a wife-beater, but his former employment in the Ebbing police department kept the cops from ever cracking down. Dixon undergoes a bit of a heel-face turn driven by his eavesdropping on casual talk of sexual violence. The callousness of characters in power towards victims is omnipresent. It wouldn’t be a McDonagh film without some blasts at the Catholic church, another source of Irish rage, and there’s a sensational slapdown here. The characters want to find an outlet for their anger and frustration, and they don’t have to look far.

Much of the Oscar talk around Three Billboards framed the film as a righteous story of vengeance against abusive men, perfectly timed to the goings-on in the Hollywood of 2017. I doubt any of those proponents actually saw Three Billboards in its entirety. Mildred is an excellent character, but the film does not exalt her actions in any way. It’s on the side of her neglected son, shattered by having to live in the shadow of billboards that graphically describe how his sister died. It’s on the side of victims of violence who don’t let themselves be consumed by what happened to them. A very simple act of charity roots the film on the side of forgiveness. Three Billboards ends on an ellipsis, where little is resolved but the future can be easily divined. In McDonagh’s telling, that limbo is what awaits those who refuse to continue on with whatever remains in the wake of tragedy. In their work, it’s apparent that the McDonagh’s hate the pedophile-enabling church but love much of the church’s teaching on forgiveness. In that vein, I’ll praise what I loved about Three Billboards and compartmentalize what is self-evidently broken about it. B+

RSS Feed

RSS Feed