A- | Two detectives hunt down a serial killer who's using the seven deadly sins as an inspiration. Directed by David Fincher Starring Morgan Freeman, Brad Pitt, and Gwyneth Paltrow Review by Jon Kissel |

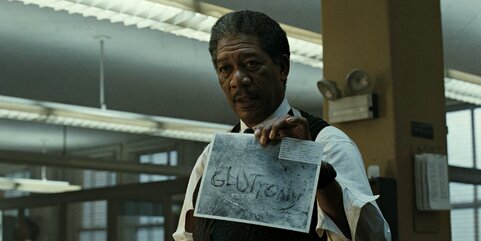

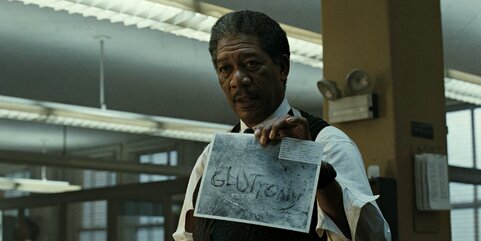

David Fincher’s first film, Alien3, infamously begins with all the hard sacrifice from its action crowd-pleaser predecessor up in smoke before the opening credits are finished. Ellen Ripley’s surrogate daughter and potential love interest that she’s both saved from the alien queen don’t survive a crash landing on a prison planet, and the movie continues without them. That kind of ruthlessness will be with Fincher throughout the rest of his career. As bleak as his debut is, he tops himself with his smash hit follow-up Seven, a serial killer noir that constructs the worst contemporary world possible and dares the viewer to find a glimmer of hope. Featuring career-changing performances from its main cast and a series of unforgettable images, Seven stamped Fincher as a major filmmaker, an iconoclast who rejected audience expectations and kept coming back to whatever fucked up thing popped into his head.

0 Comments

I once attended a lecture about South Korea exporting its culture under the assumption that it was going to be about the gonzo, transgressive films of Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho. Instead, the lecturer discussed K-pop and its unique brand of manufactured wholesomeness, a phrase totally unfamiliar to fans of Oldboy and Memories of Murder. Of course, as great as those films are, K-pop has a much wider appeal and dominates the global interpretation of South Korean culture, and I, not being a fan, am a narrow-minded fool who thinks everyone interprets culture the same way I do. It’s like if all I knew of Canada were the films of favored canuck son David Cronenberg, and expected every Canadian to have an opinion on which of the dozens of fleshy vestigial appendages in his films were their favorite (Videodrome stomach or Dead Ringers connecting tissue for me). For all of Canada’s stereotypical courtesy and niceness, Cronenberg has been his own stalwart maple tree, pumping out acidic, dystopian sap for five decades with no signs of tapping out. Scanners fits squarely within his early career, where Cronenberg is still figuring his formula out and putting the pieces together. It’s not yet the total package of body horror, corporate satire, and taboo behavior that he’ll hit on shortly after Scanners, but here, things are coming together for this cinematic master even as he’s blasting prop heads apart.

Of all the auteurs who write and direct their own movies, David Cronenberg doesn’t leap to the top of mind as the creator of personal films. His combination of body horror, cultural satire, and psychodrama is unique enough without having to read details from Cronenberg’s life into his work. With The Brood, an early Cronenberg entry made in the wake of a bad divorce, one can see that a mind as acidic as his can go to some dark and cruel places when people from his life are subbing into his movies, particularly when the protagonist’s mother is depicted as a cultish monster who’s trying to keep her kids from her ex-husband. However, perhaps it’s the getting all of his ugly feelings onscreen that puts Cronenberg on his path, moving away from the gorefests that predated The Brood and towards the richer territory of what comes after. Characters expelling their psychological baggage to transform into their higher selves is a hallmark of Cronenberg’s career, and his divorce and the film he made about it may well serve as the catalyst.

In a good-faith book exchange with my very Catholic mother, I was given a book by a Catholic historian that was a clipped history of 2000 years of popes, crusades, and Papal States politics. The author couldn’t hide his distaste for the unmediated personal relationship with god that Protestant religions advocate for, under the supposition that something as powerful as religious ecstasy had to be moderated through the giant filter that is the Catholic church. Saint Maud provides a strong argument in the author’s favor. Alone and isolated and more than a little damaged, the protagonist of Rose Glass’ intense debut Saint Maud turns to religion where previous things like booze and hedonism have failed. At least with the latter, she was slowly killing herself with alcohol instead of all at once with acetone and zealotry.

Half Captain Planet episode, half monster movie, Into the Grizzly Maze is a baffling exercise in discarded production budgets or an instruction manual for money laundering. What it isn’t is a credible story or a movie fit for release, despite the considerable amount of talent put onscreen. Billy Bob Thornton has both an Oscar and a credit for playing a bear psychologist. There’s so much great cultural output in the world. I don’t understand why anyone would waste their time on this. |

AuthorsJUST SOME IDIOTS GIVING SURPRISINGLY AVERAGE MOVIE REVIEWS. Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

Click to set custom HTML

|