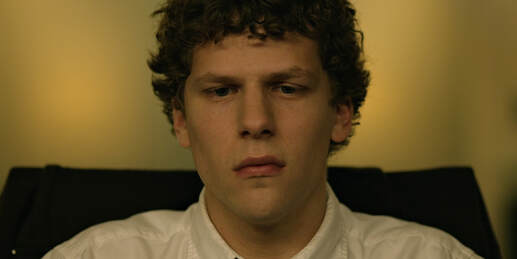

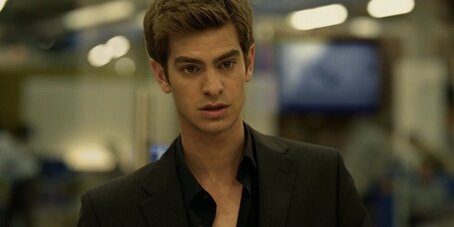

A- | The heavily-fictionalized founding of Facebook places Mark Zuckerberg against wealthy enemies and old friends. Directed by David Fincher Starring Jesse Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield, and Armie Hammer Review by Jon Kissel |

For Sorkin, Facemash is a kind of skeleton key into Zuckerberg, the kind of thing that, in the film’s final scene, makes settlement an inevitability and a trial impossible. Because he made Facemash, his reputation will always be written in ink. Sorkin then makes the biggest leap into fiction with a skeleton key for a skeleton key in the film’s opening scene, something so important to Fincher that he made Eisenberg and Rooney Mara do 99 takes of it. Mara’s Erica, a student at neighboring Boston University to Zuckerberg’s Harvard, dumps Zuckerberg after one condescending assumption too many, and within their final date, the film lays out its impression of who Zuckerberg is. He’s from an upwardly mobile family but he’s conscious of what it takes to rise to the top echelon. He’s done a lot of the work already in getting accepted at Harvard, but there are circles of the elite within the elite, and that’s where he wants to find himself. For Zuckerberg, talent is subordinate to accomplishment and accomplishment is subordinate to access. One does the great thing not because it needed doing, but because it confers power. Erica is incapable of thinking in terms of this kind of poisonous grasping, and her final straw is Zuckerberg using what access he already has i.e. Harvard admission to shine his light onto her, never considering what that must feel like for the person so fortunate to have a ‘great’ man look in their direction.

If Zuckerberg was a different person, he would soon make that realization when the Winklevii and Narendra make their pitch to him. Fresh off the notoriety of his Facemash program, they recruit him to do all the hard work on their idea of a social network within Harvard, promising that it’ll redeem him in the eyes of the campus. Despite him saying the same thing to them that Erica says to him (you’d do that for me?), there’s no implication that he’s making an empathic connection to his ex-girlfriend. Instead, this transforms his interest in the ultra-exclusive final clubs from one of desire to one of resentment, such that when Saverin is recruited by one, I read his passive-aggression towards the choice as founded in miscommunicated concern rather than jealousy. Much like his rejection by Erica spurs creation towards a misogynistic outlet, his implied rejection by the Winklevii tilts him towards the theft and democratization of their social power. The thing he can’t have must be destroyed.

A thing never needed destroying so much as the Winklevii’s worldview. It’s not important which one is the holdout, delaying lawsuits against Zuckerberg because men of Harvard don’t get down in the gutter with each other. It’s extremely important that one or both of them would feel that way. Two genetic lottery winners gestated in the same uterus, and they still think the world owes them something. Harvard president at the time Larry Summers (Douglas Urbanski) in real life is a pretty execrable figure, but by telling them off in no uncertain terms, he’s practically the hero. The Winklevii are a pair of meritocratic frauds who have no doubt worked hard but have little conception of the length of their head start, such that it renders all their labor insignificant on a larger scale. Even by Harvard standards, they’re transgressing at least the public perception of a ‘went to college in Boston’ alum. Harvard grads are supposed to play down their alma mater, at least in public, and these guys are trading on it. I believe their final line in the movie is ‘let’s gut the frigging nerd,’ finally putting the slobs-versus-snobs subtext into text and rendering them as the cruel bullies they know themselves to be.

Maybe that does fit with Zuckerberg’s pattern of destroying the thing he can’t have, which in Saverin’s case is the Harvard alumni network that probably makes up a lot of the NYC financial scene where Saverin is dialing for dollars. I’m no economist, but one way to think about the economy over the last thirty years is as a wealth transfer from one coastal center to the other, from the investment bankers of Goldman Sachs to the venture capitalists of Palo Alto. Of course, both make each other richer in the process, but as far as The Social Network is concerned, Zuckerberg represents one way of doing business and Saverin the other. The Zuckerberg who won’t put on a tie when he can be convinced to wear something other than a hoodie would never be taken seriously in a Manhattan boardroom, but he might be the third-best-dressed in a West Coast innovation hub. These changes in questions from ‘are you making money now’ to ‘might you make money in the future’ are fundamental to the tech industry, such that the biggest disruptors of the last five years like Uber or Snapchat have never made a profit despite ballooning valuations. Zuckerberg doesn’t destroy the suit money in New York, but he has, in his words, the minimum amount of attention towards it, and to Saverin’s plans by extension.

What seizes Zuckerberg’s attention is the antithesis of Saverin and his business dreams: an unemployed, pseudo-homeless, self-described entrepreneur who we meet having one-night-stands with coeds. Justin Timberlake’s Sean Parker is Zuckerberg before Zuckerberg, albeit a less-successful version. Upending industries before he’s 25, Parker is one of the first tech disruptors, and he’s able to transcend his body’s geeky failings (allergies, asthma) in a way Zuckerberg can’t. The film imagines him as a Faustian figure, convincing Mark to trade what’s good in his life (Saverin’s friendship) for larger success with even shadier figures (hello, Peter Thiel). Through Parker, the film’s conception of Zuckerberg becomes even sadder, as Parker, perhaps falsely, also traces his origin story to a failed relationship. The difference between the two is that Parker doesn’t think about that girl anymore.

Portraying all of this and a lot more is the core cast of Eisenberg, Garfield, Timberlake, and Hammer, each great in their own way. What they share is a character who is acting in a way that makes them despicable, but each respective actor is doing something that makes them forgivable. Eisenberg whips out a cuddly sadness a handful of times that keeps him from being a robotic sadist with no inner filter. Saverin’s reckless naivete is leavened by a genuine concern for Zuckerberg that Zuckerberg has no ability to reciprocate. Timberlake is bursting with goofy charisma; his ‘it’s cleaner’ line is correct in thought but so absurd and pretentious in its delivery and he plays it like he knows all three things. Hammer has exactly the same kind of energy as the characters on Succession do: I desperately want him to fail but I’ll gleefully watch him for however long it takes.

The Social Network has the occasional clunker of a line and a needlessly characterized Brenda Song as Saverin’s crazy girlfriend, so I’m going to downgrade it slightly from its previous state of perfection. However, this has continued to resonate as one of the best and most important films of the 21st century. A technical marvel in its portrayal of the Winklevii, an acting showcase, a unique blending of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ score with the mental state of the characters, some of Sorkin’s best dialogue, and the guiding hand of master filmmaker Fincher make the legal quibbles of a website’s creation as kinetic as a high-octane action flick. It’s also a definitive story of dissolved friendship and divergent vision, a warning against a kind of behavior that will only continue to metastasize from 2010, and an always-needed reminder of how much power we’ve put into hands who are uniquely unqualified to wield it. I wish the film had a little more of the messianic quality that Zuckerberg continues to demonstrate, but The Social Network has its finger on the rapacious, narcissistic, and misogynistic pulse that drives so much of the tech industry and America by extension. The Victoria’s Secret anecdote rings out as something unique to this country, where a multi-million dollar payday would be cause for suicide. Maybe that’s the sentiment of a person who’s never going to build much of anything in their life, but it’s also the sentiment of a person who’s not gnawed at by inferiority. It’s incredibly fitting that a person so incapable of contentment created a thing that makes it that much harder for the average user. A

RSS Feed

RSS Feed