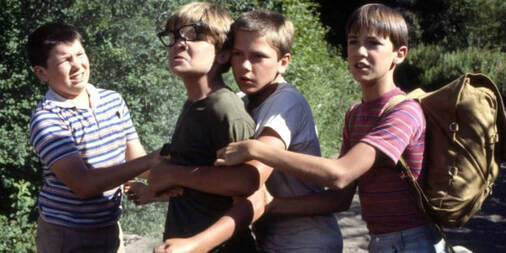

A- | Four boys hike through the woods in search of a missing kid. Directed by Rob Reiner Starring Will Wheaton, River Phoenix, and Corey Feldman Review by Jon Kissel |

The ability of the boys to disappear for days is so taken for granted by the film that there’s not even a perfunctory scene of them concocting a lie to tell their parents. Reiner, who would’ve been exactly the same age as his main characters in 1959, understands the amount of effort needed to do something like this, and it’s not very much. Parents had more faith in the world, or reliance on the resilience of children. This is despite the fact that the film’s adventure revolves around a kid, Ray Brower, who died alone in a forest. The death of Ray isn’t going to change anything in the town. Kids will still be expected to get the hell out of the house during the day and return at night. What changed this culture is a decades-long project of media and politics, and now a significant portion of parents are going to be looking through their children’s Halloween candy for fentanyl. There’s a level of stupidity in no supervision, but there’s a greater amount in hypervigilant mania. Films like Stand By Me that communicate how American culture used to trust both children and the community work on even a viewer like myself who considers themselves immune to nostalgia.

The kids aren’t the problem in Stand By Me’s little community. The adults, however, are a mess. It’s been fourteen years since WWII ended, and it’s reasonable to assume that all the central kids’ fathers served and were perhaps deeply affected or damaged by what they saw and did. This being the 50’s, no one’s able to talk about any of it and no one really wants to hear it anyways on account of WWII being the good and noble war. Why tarnish that public mythmaking with anything but stoic acceptance and annual parades? With the possible exception of Vern, the other kids have fathers that range from brutal to distant. Gordie’s dad makes little secret of how much he preferred his older son, while openly sharing how much disdain he has for Gordie’s friends and hobbies. Chris’ dad drinks to the point of blacking out, and Teddy’s dad mutilates his son when he’s not bouncing between mental hospitals. Non-parental adults are just as untrustworthy, from the teacher who lets Chris take the blame for stealing the milk money while pocketing the cash herself to the junkyard owner who drives Teddy to the point of insanity with his taunting. Stand By Me places the boys at the cusp of junior high, but they’re going to continue to move through less-official gates that inform what kind of men they’re going to turn into: the poor example of their role models or something better.

In the moral universe of Stand By Me, whether or not a person is going to break out of an emotionally stunted milieu is determined by their ability to be honest about what makes them feel vulnerable. The film appreciates Vern as a good-natured dope without much of an inner life. His breakdown is nothing more than in-the-moment fear. Stand By Me’s far more interested in the other three friends. Teddy’s a boiling pot of hair-trigger anger, unpredictable and reckless. His meltdown is triggered by the junkyard owner insulting Teddy’s father, the same man who burned his ear off on a hot stove. Teddy has the opportunity to resolve this paradox with his friends, but he changes the subject. Gordie and Chris will be okay because they’re able to trust each other with anything other than strict masculinity. Gordie feels alone in his own home because he’s sure his dad hates him, and Chris is dogged by his older brother’s bad reputation. They’re bonded closest together not because of this trip they go on, but because they’re able to cry on each other’s shoulders and allow themselves to be comforted.

Casting kids has got to be one of the harder parts of making movies, and Reiner has talked about lucking into the central foursome. Each were similar enough to their characters that the job was mostly done before shooting. O’Connell had great comic timing for a tween, Wheaton was insecure and shy, Feldman was angry thanks to his exploitative parents, and Phoenix was a soulful and effortless leader the other boys wanted to impress. O’Connell is outclassed by his more experienced peers, though the film asks the least of him. This is the only thing I’ve ever liked Feldman in, probably because he’s being cast as someone painfully similar to himself as opposed to a smart aleck neighbor kid. Wheaton physically embodies the ‘sad kids are sad’ cliché that always works on me. There’s an early shot of him walking down the street alone that says everything necessary about his character. Phoenix is great every time I watch this film, worthy of Gordie’s idolization of the character. A less earnest version of Chris wouldn’t be able to sell how patient he is with Gordie, justifiably mopey since the loss of his brother, but Phoenix is incapable of irony and he’s glad to buck up his friend every time it’s necessary to do so.

The last line of Stand By Me is in deep danger of corniness, but the film earns it by making this more than an eventful journey from point A to point B. It wouldn’t work in the Goonies but it works here. This is by no means a perfect film. Adult Gordie’s narration is as bad as narration gets, and the character only seems to exist so that last line can be delivered. The film lightens the book ending, where Ace and company kick the shit out of the kids and all but Gordie die in young adulthood. I can overlook that and more because there’s emotional truth here, the embodiment of an oft-thought of article about how male relationships are at their strongest during this age and the rest of a man’s life is spent in mourning for these kinds of friendships. The film’s last line didn’t know it at the time, but it was unearthing a sociological truth. A-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed