A- | Two detectives hunt down a serial killer who's using the seven deadly sins as an inspiration. Directed by David Fincher Starring Morgan Freeman, Brad Pitt, and Gwyneth Paltrow Review by Jon Kissel |

The three main characters push back against the killer in different ways, all ultimately ineffective. Detective David Mills (Brad Pitt) brings bravado and naivete to the table, insisting that the killer is merely crazy and therefore outside of the realm of understanding. He’s full of anxious statements that fill the silence and thought-terminating cliches to cover up for his refusal to engage. His wife Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow) is clearly the brains of the operation, a better person than her husband and therefore willing to indulge him in what he imagines as his big break. The couple both embody hope, but she has to work harder to generate it. By staying together and starting a family, they’re acting optimistically, even if Tracy doesn’t yet feel it in the same way her husband does. In opposition to them both is weary Detective William Somerset (Morgan Freeman), a week away from retirement and anxious to get there. Utterly alone in the world, Somerset has nothing to offer the Mills’ except for the promise that one day, they’ll go numb. His career and his life has made him apathetic, and he hates that it’s happening. The only good thing that happens in Seven is that Somerset is able to share some truth with Tracy, and it comes across as such a monumental moment that it may as well be the great miracle that the killer talks about.

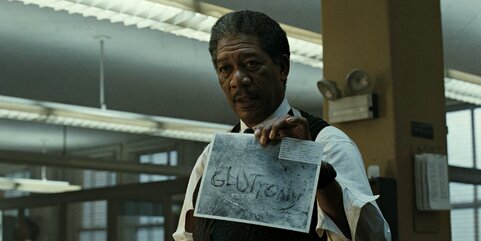

Where the moral universe of the film leaves something to be desired, Fincher’s strengths as a director are coming into focus. His utility with actors isn’t fully there, based on Pitt in the least effective of his three collaborations with Fincher, but Freeman and Paltrow are both excellent. It’s easy to forget Paltrow, with all her present-day inanity, could steal a scene from Morgan Freeman, but here she is doing exactly that. There’s several tiny parts in Seven that could credibly be called the best thing in that actor’s career, particularly Leland Orser as a man who left that interrogation room and immediately killed himself. Actors often talk about how their job is easy when they show up on a precisely designed set, and that must be true with Seven, a film that provides its cast many opportunities to look uncomfortable. This is about as gross as a movie can be, not just in what happens but in the places those things happen. The sloth victim’s apartment or the gluttony victim’s house are masterpieces of urban decay, while the killer’s apartment is packed with detail. Seven is the last film that needed to be infused with sense memory but one can easily conjure up what Mills’ dog room smells like or the feel of a gun barrel pressed to your forehead in the rain. These are all skills that Fincher’s going to hone over his career. Seven finds him most of the way there, but so much is going to improve. The man who directed Zodiac or the Social Network would never allow the just-so plot machinations that make this film move forward.

Fincher will revisit anti-social filmmaking a few years later with Fight Club, but despite the presence of confrontational dick pics, that film is far more mature than this one. Both Seven and Fight Club are a rejection of different versions of 90’s America; the decayed east coast and the vapid west coast and they both end with a dead yet successful prophet of mass destruction. However, Fight Club’s the better film because it keeps the seductive narrative at a distance. There’s a lot in Fight Club that undercuts Tyler Durden. John Doe has no real adversary. The viewer that takes Fight Club at face value and ignores its deeper place as a foundational anti-indoctrination tract is the same person who would make Seven, a film that’s more thematically elevated than Boondock Saints but by less than you think. B

RSS Feed

RSS Feed