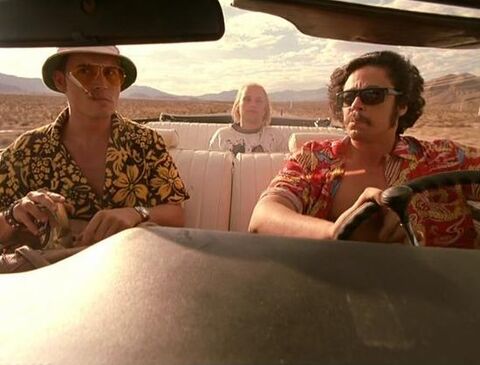

B+ | A journalist and his attorney spend a drug-fueled week in Las Vegas. Directed by Terry Gilliam Starring Johnny Depp and Benicio Del Toro Review by Jon Kissel |

When inventorying their drugs, Duke’s unreliable narration calls out ether as the worst of the bunch. A different movie would’ve saved their inevitable huffing for the end of the film, but here, they’ve lost motor control under ether’s influence after about a half hour. There’s no limit on the escalation here, so may as well ramp up quickly. Gilliam and cinematographer Nicola Pecorini used different camera techniques for each drug effect, and they get plenty of chances to mix it up. Dutch angles and fisheyes are obvious, but there’s all kinds of audio and visual distortions alongside a choppy placement of scenes that recreates all the time the two leads have lost. Having never done any of the onscreen drugs, I can’t speak to the film’s authenticity, but it feels like the real thing. Depp and Del Toro dive into the performances, acting as physically and mentally out of control as possible. Their two hotel suites each get turned into cell blocks from the movie Hunger by the time they’ve checked out, and the unpredictability of their behavior, especially Gonzo’s, makes each scene dangerous. They both attend a nonsensical drug seminar full of pseudoscience, but would the real effects of mescaline sound so different from what the crackpot police stooge is ranting about?

For people like Duke and Gonzo, the 60’s are the freeing of society from arbitrary behavioral limits, especially for anyone in the upper strata who can rub shoulders with drug luminaries like Timothy Leary, briefly seen in a flashback. The film and perhaps Thompson’s book itself diagnoses that benefit as the eventual death blow. What does Duke have to offer the average person in Vegas? Your hotel room too can look like an open sewer. The person with the disposable income to travel to Vegas is one unconvinced party, but the greater faction is all the working people who Duke and Gonzo terrorize during their stay. Duke laments the death of the dream, but he’s also a generational writer who can do his job while high. What about the waitress Gonzo terrorizes, the waiters they throw coins at, the maids who have to clean up after them? Their intense disdain of workers makes the big victories Duke mentions into Pyrrhic ones, as they alienate potential allies and drive them towards the true scum i.e. the frothing sheriff whose rage over a lost reservation almost drives himself and his wife into a heart attack.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas opens with a quote about turning into a beast to get rid of the pain of humanity. The sheriff heard in passing as he brags about killing protestors at Kent State is doing this, and despite finding that guy to be the lowest of the low, Duke and Gonzo are right there with him in adherence to that quote. Duke’s pain comes from knowing that it’s over, that whatever you hoped the country and its people might turn into is dead, and the electoral routs and police brutality and neoliberalism that comes after can only be dealt with through chemical alteration. Both he and Gonzo can be heard grunting and groaning like animals, earning the side-eyes from Vegas denizens as surely as Duke and Gonzo are side-eyeing them. This is an ugly film with a proto-black pill message, made less depressing by Gilliam’s audaciousness and the full commitment of Depp and Del Toro. As occasionally funny as it is to watch Duke melt his brain with ether, the film’s sour taste is its hangover but then, who could look at the last 50 years of America and feel anything different? B+

RSS Feed

RSS Feed