C+ | Elvis Presley's conman manager reflects on his career on his deathbed. Directed by Baz Luhrmann Starring Austin Butler and Tom Hanks Review by Jon Kissel |

For every laughable zoom that Luhrmann uses, like the aforementioned ‘he’s white?’ one, the leaden camerawork of Elvis sometimes finds a way to succeed. This is a film of powerful moments with a lot of trash in between. Luhrmann will find a woman at an early Elvis show who’s barely keeping it together and then zoom into her face, like the camera is giving her permission to lose control and she obliges with the same kind of ecstasy that marked young Elvis’ experience in a sweaty tent revival. A primary objective of the film is to convey what it would’ve been like to be freed from inhibition by the power of an Elvis performance, and Luhrmann uses every intrusive filmmaking technique he can muster to do exactly that. There’s no room for subtlety or restraint in speaking in tongues or screaming from deep within your body, and if that’s going to be the film’s stock in trade, it’s not going to have those things either.

Eugene Jarecki’s road documentary The King borrowed one of Elvis’ Cadillacs and drove it across the country while extemporizing how Elvis’ life mirrored the path the country took in the post-war period. He kept striving for greatness but would always get bogged down by what fed his appetites, thus trading the best version of his career for chintzy movies and Vegas shows. That narrative weighed heavily while watching Elvis, but Luhrmann and his three co-credited writers frame their Elvis as a pawn in the Colonel’s game. The time wasted in Hollywood and Hawaii is skipped over. There’s no criticism of his profiting from the work of overlooked Black artists, though the film clearly delineates how he stole and creates scenes where he might’ve been confronted on Memphis’ Beale Street. Instead, these places are a haven for him where he can recharge away from the spotlight. It’s credible that the Elvis of the film would find camaraderie with his Black neighbors and contemporaries, but that friendliness also means that they would be comfortable confronting him about his intellectual property theft. The film is better with Elvis’ Vegas term, a deeply sad affair that begins with a joyous Elvis composing his famous stage opening in one of the year’s best scenes. As the first show is going off beautifully, the Colonel is in the audience, inking the deal that will anchor Elvis there until his death. Luhrmann emphasizes the Colonel’s villainy instead of Elvis’ complicity, a tactic that matches the film’s operatic nature while also eliding the musician biopic trope of chemical-addled decompensation.

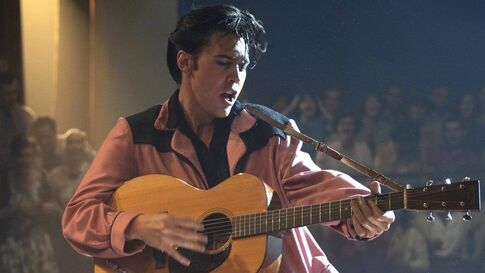

Musician performances so frequently get elevated by all the worst crutches of awards bodies, from physical transformation to the impersonation of a historical figure and the added difficulty of singing and dancing. Butler’s doing all of that, but at a volume that drowns out all the inferior musician performances. He’s incredibly charismatic in the role, and constructs a mythology for Elvis’ style of dancing. Butler plays him like he has no actual control over his body when the spirit takes him onstage, going into fits and spasms that come out in the rubber-legged punctuations that Elvis was known for. The physicality of the performance is striking, like Butler is going to hurt himself with the force of his gyrations. No one else by comparison is particularly memorable due to Butler’s wattage. Hanks is doomed by the accent, and the supporting cast seems to have been chosen for their ability to melt into the background, with the exception of Kodi Smit-McPhee in a small role as an early Elvis imitator. Butler blows everyone else off the screen, and is the first one of these musician biopic performances in a long time that I’d be perfectly fine seeing rewarded.

The marriage of Butler’s charisma and Luhrmann’s flair eventually snow the viewer into thinking they’re seeing something better than it is. Luhrmann should stay as far away as possible from anything adjacent to the civil rights era, and his attempts to sync Elvis’ journey with the events of the late-60’s are painful. The film surprisingly draws a coherent line between repressive 50’s politics and a staid cultural output, like the former can’t survive without the latter, but like the gambling addicted Colonel, Luhrmann can’t quit when he’s ahead. Nevertheless, if seeing Elvis perform transcends language and devolves into animalistic screaming, the movie about him might have to be ultimately judged by how it makes the viewer feel. My connection to Elvis, despite everything I know to be wrong with it, is one of 2022’s biggest surprises. I’d have sooner expected to well up in Lyle, Lyle, Crocodile than this, but here we are. B-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed