B+ | A first-hand account of two controversial sexual assault cases. Directed by Bonni Cohen and Jon Shenk Initial Review by Jon Kissel |

The interviews are the reason for the film’s existence, and Cohen and Shenk pad out the running time with a similar event. The Daisy Pott of the title, another victim of a drunken sexual assault, is in a more traditional documentary, but an equally effective one. Cohen and Shenk compile police footage and compelling visual language in their B-roll shots to augment the sheer human drama of Daisy and her family’s story. Her changing appearance over the years is a more effective demonstration of roiling inner turmoil than her plaintive Instagram posts. There’s so much cultural rot in Audrie and Daisy, from the Instagram sext stash at Audrie’s school to the fate of the Pott family. The brother, a baseball coach, serves up an example of how culture gets changed by not allowing his players to speak crudely and disrespectfully about women. What’s acceptable in conversation rolls downhill towards action, until one of those young players is intimidating a 14 year old girl into drinking far more than a person is capable of.

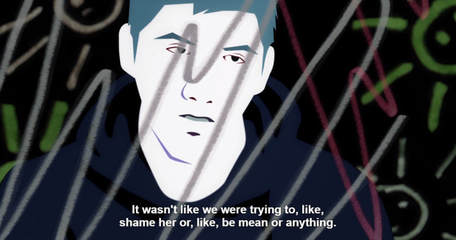

The callow nature of the perpetrators and their enablers is again made apparent in Daisy’s story. This is some banality of evil stuff. In the police interview with Daisy’s rapist, the detective thinks he’s going to trap him in a lie about not knowing how old she was. Nope, he knew the whole time, didn’t think anything of it. On the police side, it’s impossible to be able to determine the truth from the sheriff who devolves from a straight shooter into someone who’s subtly praising the convicted and slandering the victim. Now, everyone can get back to watching the football team again. The film Melancholia was recently on my mind, in which a planet smashes into the earth and destroys it. Kirsten Dunst’s character, a chronically depressed woman who welcomes the apocalypse, says, “The earth is evil. We don’t need to grieve for it.” Seeing communities take the obvious wrong side are occasions to cosign to such a sentiment. The Joe Paterno riots on Penn State’s campus are one example, and the way the town treats the Pott family is another. They so readily take sides and make the Pott’s family’s lives into living hells with hashtags and vandalism and arson. I just don’t understand the kind of thinking that would cause a person to be so cruel. That’s the documentary that’s needed: interview the people who so readily celebrate guilty pleas and attack the victim.

The smaller role that the Internet plays in Audrie and Daisy puts the film into its present day context. Audrie’s chat records indicate someone who thought what happened to her would follow her around indefinitely, a digital scarlet letter. The boys who pass around her pictures think nothing of this and tell her she’s overreacting. Daisy’s ordeal is the classic version of cyberbullying where there’s just nowhere for her and her family to hide. Where twenty years ago, assholes might’ve looked askance at her in the grocery store, now they rail viciously on Twitter at all hours, a public record of their insufficiency as people but one that makes them feel important for harassing a person they see as a harlot. Again, I don’t get this form of behavior, at all. I don’t understand how someone could pester an acquaintance for naked photos and I don’t understand being a part of an online lynch mob.

There’s a telling moment early in the film where Audrie’s best friend talks about how she was never asked for naked pictures because she developed late. She giggles and laughs it off before becoming deadly serious about how she told Audrie to never send anyone anything. It’s self-deprecating laughter that contains some small amount of hurt. Why didn’t I get the kind of attention Audrie did? That’s how poisonous this all is, where an individual can feel slighted for not being asked to participate in a douchebag’s spank bank. This documentary is the validation of Herzog’s most pessimistic stance. The Internet, as a tool in Audrie and Daisy, doesn’t do anything for anyone beyond comfort the powerful and afflict the aggrieved, and the only solution proves to be family and in-person support from people who’ve gone through the same thing. B

RSS Feed

RSS Feed