C | A disgraced UFC fighter is hired as a bouncer at a rowdy Florida Keys bar. Directed by Doug Liman Starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Conor McGregor, and Daniela Melchior Review by Jon Kissel |

I haven’t seen the original Road House, though it gets mentally grouped in with the muscly action trash that dominated the 80’s. Maybe it’s better than the Commandoes and Cobras of the world, but it sits comfortably alongside its genre buddies with their big body counts and hacky quips delivered in a Schwarzeneggar accent, Stallone mumble, or Seagal whisper. Present-day action filmmaking is too cloaked in irony to pull off the same kind of tone, preferring a that-just-happened incredulity to the you’re-damn-right-it-did swagger of the Reagan/Persian Gulf era. It’s therefore interesting to see what a modern remake of Road House might look like, and how that 80’s tone translates to current sensibilities and filmmaking trends. However, Doug Liman’s adaptation is fruit of a poisoned tree. As Hollywood moves away from superhero movies and is in search of its next big blockbuster trend, let’s hope they leave the 80’s in the rearview where it belongs.

0 Comments

Of the major global outposts for movies, India is the one I’ve had the least experience with. I’ve seen two Satyajit Ray films from the 50’s (both great), The Lunchbox starring Irrfan Khan (pretty good), and, most indicative of India’s cultural exports, 2022’s RRR. That last one is what most think of when they imagine the work of Bollywood/Tollywood; epics with frequents musical interludes and intricate dance numbers. RRR was a strong introduction to this kind of filmmaking, though it’s not the kind of cinematic empathy-building that I’ve found in countries as varied as Brazil, Romania, Iran, and South Korea. Indian non-musicals, removed from the heightened nature of the genre, seem few and far between, and that’s generally what I want in my foreign film-watching. Monkey Man, from actor/writer/director Dev Patel, isn’t exactly that, as it’s a bloody revenge flick with plenty of choreography, just not the kind that everyone dances to. It does, however, give a peak into a culture and a nation that I feel like I should know more about, given its place in the world, while also delivering on the martial arts ultraviolence of its genre predecessors.

Tom Cruise is a movie star who insists on getting things right. No matter what the audience thinks about his role as highly placed cult official, he’s undeniably a craftsman who takes immense pride in his work, even at the risk of his very expensive safety. It therefore seems inevitable that he would star in a period vehicle that elevates and valorizes a Japanese ethic of expertise and excellence, especially in the immediate years after filming Eyes Wide Shut with Stanley Kubrick, he of the endless, repetitive takes. Cruise finds the perfect historical epic that both validates his approach to work and turns him into the adaptable genius who is capable of mastering anything. In its subtextual flattery of Cruise, The Last Samurai, directed by historical epic veteran Ed Zwick, smells like a more pungent variety of white savior trope than it actually is. The film itself works as one of the best examples of white-man-meets-foreign-culture. It doesn’t totally avoid the various pitfalls, but it skillfully navigates them.

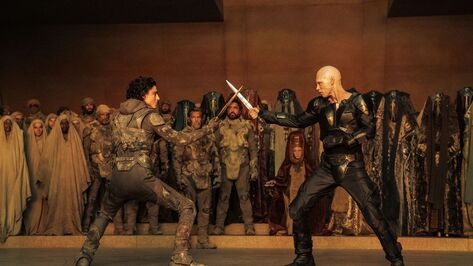

As big-budget filmmaking finds itself at a crossroads, where the cash cows of the past have been put out to slaughter and no one knows what the next billion dollar film will be, every film that smashes expectations creates a possible future where movies like itself will one day be the next exhausted fad. Will it be historical biopics with all-star casts, weightless video game adaptations, satirical toy tie-ins, or jingoistic advertisements for the military industrial complex? Denis Villeneuve imagines the possibility that the wave of the cinematic future is superficially opaque space operas, where invented terminology like kwisatz haderach and lisan al-ghaib are made to sound meaningful instead of ridiculous. His two Dune films, with a third on the way, use the bludgeoning effects of size and scale to make the theater experience a must, but Villeneuve also remembers the human element, even moreso in Dune: Part Two. Frank Herbert’s novel is a recognizable hero’s journey, partly because it’s a classic story and partly because so many subsequent stories have imitated it, but the specific influences of the book and what Villeneuve chooses to embellish and focus on makes Dune into a hopeful harbinger of a better cinematic future.

Some of the best documentaries of the 21st century have incorporated some kind of meta element into their storytelling. The Act of Killing got its Indonesian government-backed murderers to consider their actions through filmmaking, while The Witness and Tower took innovative approaches towards recreating infamous events from the 1960’s. Dick Johnson is Dead and Procession got their subjects involved in acting out their own fears and traumas, or those of the director. Kaouther Ben Hania’s Four Daughters is in this tradition, breaking up a standard talking head format by casting actors as two of the four titular women. This serves to make the subjects more vulnerable in telling their complicated and affecting story of patriarchy, abuse, and fundamentalism in pre and post revolutionary Tunisia. |

AuthorsJUST SOME IDIOTS GIVING SURPRISINGLY AVERAGE MOVIE REVIEWS. Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

Click to set custom HTML

|