The return of Palpatine, especially after The Last Jedi set up Kylo Ren as the Disney trilogy’s final boss, is a meaningless development that’s revealed during the series’ opening crawl, and it’s a major sign that the film is not going to treat its audience like intelligent moviegoers. There’s been little to no prior evidence in episodes 7 and 8 that this character was going to reemerge. It’s simply a boring choice to make everything directed from the shadows, again, by a character who is evil for evil’s sake and has no greater shading than a desire to dominate everything. To their credit, the prequels were essentially Palpatine’s years-long efforts towards corruption and ultimate victory. He just shows back up here. Palpatine also raises the specter of resurrection that the film proceeds to abuse, and like every other story with resurrection in it, it makes death a lower-stakes possibility. Characters that are believed to have been killed or, in the case of droids, have their memories blanked are in fact alive or have backup files, and the Force can now be used to heal. The Last Jedi brought in Force projection as its new power, but that served to bring distant characters together for deep conversations: Force resurrection is just cheap.

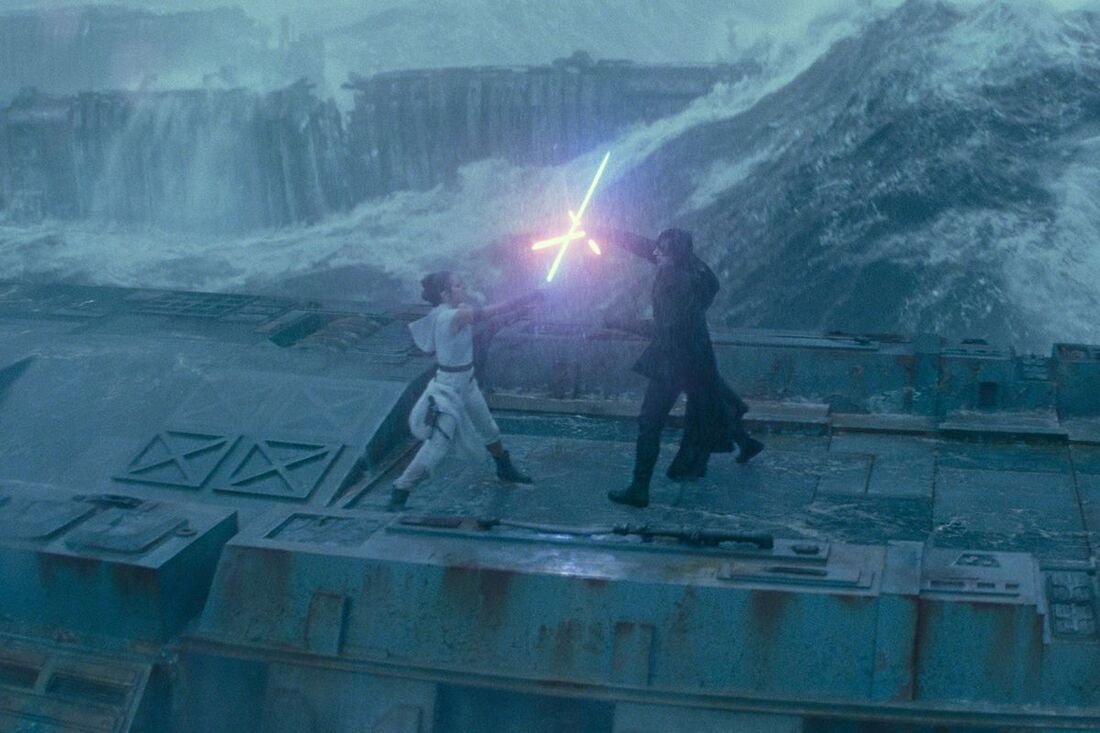

If Abrams and company are going to bring back the franchise’s main evil mastermind, that at least provides an opportunity for some big fireworks. However, the action is unimpressive and another series’ lowpoint, with predictable turns of fortune and last-minute saves that are pitched as rousing moments but land with a thud. The Rise of Skywalker suffers from the same abuse of this trope that Peter Jackson’s Hobbit movies did; by the fifth or sixth rescue, the trope has lost all its power. Abrams also makes a spatial mess of the geography of scenes, letting characters get away when they are surrounded or cornered or just hand-waving escapes by cutting to the next scene. The elongated climax takes place with lightsaber duels on the ground and space battles in the sky, and neither hold up against recent or decades-old series high points. If someone was making a listicle of Star Wars’ best sequences, it’s difficult to imagine them including anything from Rise of Skywalker.

Abrams even fails to follow through on intriguing incorporations he made in The Force Awakens. Finn’s backstory is that he’s a child soldier abducted by the First Order and made to be a storm trooper, and The Rise of Skywalker continues to introduce characters with similar plights. However, the obvious yet unconsidered problem is that every time the characters gleefully murder platoons of storm troopers, they’re taking out brainwashed victims that Finn might have once sat down and shared a laugh with in the mess hall. The film has to stay true to the original trilogy’s frivolous tone by making the enemies into Keystone Kops who can’t shoot straight, but they’ve also provided a thin, self-congratulatory sheen of complication that they don’t do that much with in the first place. Neither Finn nor Poe are memorable presences here in a complete waste of Boyega’s and Isaac’s considerable powers.

Ridley and Driver bear most of The Rise of Skywalker’s acting weight, and, like in their two previous films, they carry it well despite their increasingly muddled characterizations. The introduction of Palpatine relieves Driver’s Kylo Ren of the responsibility of being the main antagonist and neuters what appeared to be a more out-of-the-box arc. He and Ridley’s Rey both slot into traditional, unsurprising archetypes as the saga reaches its finale, which isn’t to say they become as bad as the writing. Driver loses the petulant frustration and becomes more placid and focused, while Ridley conveys inner torment and resilience in the face of said torment. Both are more deserving of where the series leaves them.

In wanting to make the least challenging version of itself after the overwrought internet-nerd backlash to The Last Jedi, a film that incidentally earned critical raves and a third of a billion more than The Rise of Skywalker, Abrams has put a sloppy period on a beloved series and consigned it to a derisive, mercenary, mediocre place. He ends his film with a recreation of one of Star Wars’ most iconic scenes, and, based purely on residual goodwill, it works, or at least it does until one realizes that there’s no reason for it to exist within the onscreen context. Abrams clearly wanted to send his audience out with a saccharine bump of nostalgia, but he instead crystallized exactly what’s wrong with his film, and by extension The Force Awakens. It has no deeper meaning or purpose beyond reconnecting to something the audience has fond feelings for. That, and the generation of around four and a half billion dollars. C-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed