|

Laura Poitras makes documentaries about people fighting against great odds. The transparent rightness of their cause is never enough for her protagonists, some of whom eke out hard-fought victories while others are crushed by the antagonist, which is always the US security state. Her efforts have landed her on government watchlists, adding a second layer of prosecution to what the US wants to keep secret. Documenting the documenters can make one’s life difficult and dangerous. In Poitras’ latest, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, she steps away from government malfeasance and into the bottomless well of corporate crime. Her vessel into this new world is photographer Nan Goldin, a witness to American repression and cultural rebellion who’s been at the center of major 20th century cultural phenomena. Poitras’ arrangement of Goldin’s life and work is a consciousness-broadening experience, a confrontational redefinition of obscenity and transgression. It’s not the you-are-there reportage of Citizenfour, but a historical journey that, for once, culminates in a victory.

0 Comments

The story of the last ten years, and the next hundred, has been and will be migration. Political instability, economic privation, civil war, environmental collapse, it all conspires to push people into stable places that often contributed to or directly caused the instability that made migrants and refugees flee in the first place. Flee is the story of one of these families torn between great powers and cast into an underground morass whose effects linger long after safety has been achieved. Jonas Poher Rasmussen blends documentary and animation in a film that dissects all aspects of the refugee experience, from the uncertainty to the powerlessness. People need to get more acquainted with these kinds of stories because they’re not going to stop happening.

Shaul Schwarz’s documentary Narco Cultura tracked the mid-2010’s connection between ruthless drug violence and the celebratory musical culture that arose around the cartels. It didn’t lack for revolting people who made their living off of exploitation, and with Schwarz’s follow-up Trophy, he finds more of the deeply hate-able. Schwarz and co-director and cinematographer Christina Clusiau gets honest and chilling access to players in the big-game hunting industry, criss-crossing the world from Texas to South Africa and Zimbabwe and meeting game wardens, conservationists, and the hunters who either support or bedevil both. Trophy complicates an issue that most people have a knee-jerk reaction to, both supporting and contradicting those who are revolted by big-game hunting or who see it as a necessary expression of nature and culture.

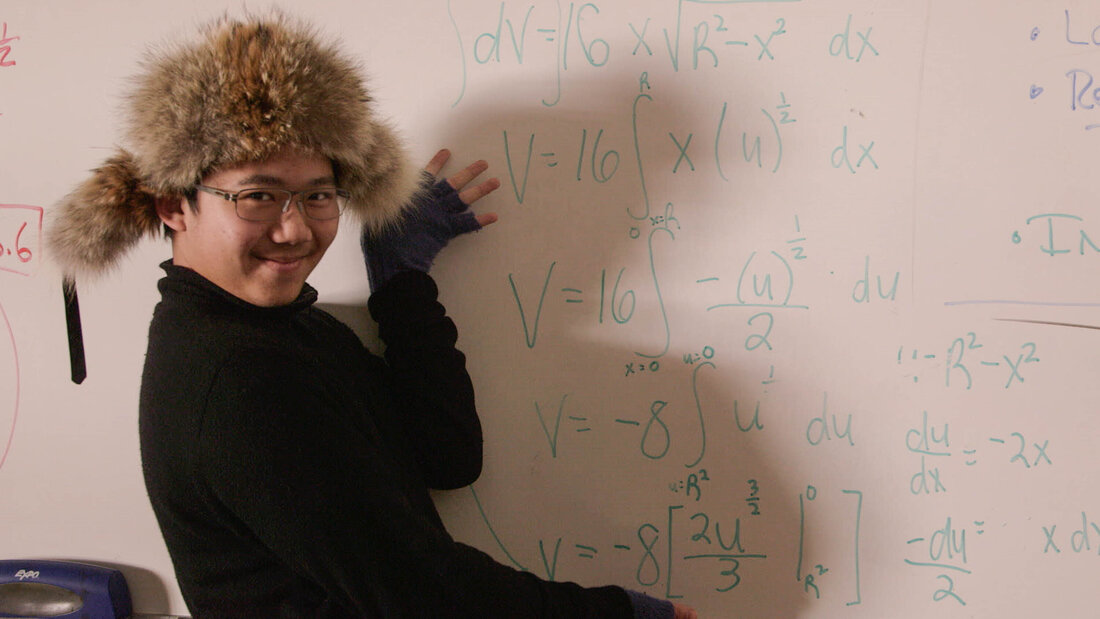

Students at San Francisco’s top-ranked Lowell High School are struggling with an amount of academic stress that looks cruel and unrecognizable. At this viewer’s Catholic high school in southern Indiana, upperclassmen competed for parking spots, not high-stakes entry into elite universities. In Try Harder, Debbie Lum follows several seniors as they polish their resumes and their interview skills, all while considering the elephant in the room of how their race is helping or hurting their chances for something they aren’t sure they even want. This is a fascinating look at the next generation’s world-beaters, unless they burn out in their 20’s under 6 figures of student debt.

With Morgan Neville’s previous documentary on the life of Fred Rogers, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, I hadn’t been watching Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood on and off over the previous months, so all the clips of the show Neville used in his film didn’t seem repetitive or overdone. There aren’t small children in my home who need the comfort of factory tours and Daniel Tiger that I’m overhearing in the background. Thanks to the pandemic and a never-ending need for more content, that’s not the case with Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown, currently available in its entirety on HBO Max. This was a series I was actively revisiting in the wake of Neville’s newest documentary, Roadrunner, a biopic about Bourdain’s life that used many of the same clips from episodes I had just watched at home. This is the most personal and happenstance of all the flaws in Neville’s film, his first miss since winning an Oscar for 20 Feet From Stardom. Roadrunner provides little insight into Bourdain that he didn’t freely offer up himself, while also serving as an offensive hit piece and a speculative attempt into Bourdain’s suicide. It seems impossible that a subject of such introspection could be dissected in this thin of a manner, but that’s what Roadrunner serves up to its audience.

Documentaries don’t tend to give me nightmares, though I’ll add the caveat that I’ve never seen the one about sleep paralysis that’s supposedly the most terrifying film of the 21st century. Petra Costa’s The Edge of Democracy lingered in my subconscious for a long time, to the point where I was having stress dreams about vicious mobs of burly men in yellow and green. Costa blends her own familial background with a propulsive story of 21st century Brazilian politics, spinning a yarn that considers centuries of history against recent events. It’s a story of collapse and retrenchment, of political icons tarnished and humiliated by their repulsive enemies, of the elevation of those who have a diametrically oppositional worldview to basic humanity. Thankfully, Americans have no way to relate to anything depicted here.

The second of Joshua Oppenheimer’s landmark documentary duo on the 1965 Indonesia leftist purge, The Look of Silence flips the perspective from those who did the killing to the relatives of those who were killed. In Oppenheimer’s earlier Act of Killing, he gets some of the perpetrators, responsible for the deaths of somewhere between 500,000 to a million Indonesians and presently celebrated as national heroes, to recreate their deeds under the guise of a mythic film. Bragging to a foreigner about what they did in that very strange and chilling film is one thing. There’s a level of distance that Oppenheimer creates that allows the killers to be completely free in what they say. With Look of Silence, Oppenheimer brings along a man whose brother was killed and lets him do the talking. These two films, each inseparable from the other, are required viewing for any thinking citizen. Darkly compelling and deeply human, Look of Silence is the antithesis to the hellish upside-down world of Act of Killing, a world that dominates Indonesia but festers with barely-contained rot and resentment.

For Sama stands alongside documentaries like Citizenfour in depicting the first draft of history. The best of breed of the several Syrian Civil War docs that have chronicled a brutal and bloody period of the 21st century, Waad al-Kateab’s first-person film tracks the initial ecstatic hopes of revolutionary optimism through its fatalistic destruction in the bombed-out husk of Aleppo. For an extra dose of you-are-there urgency, al-Kateab’s husband is a doctor drowning in emergency triage and surgery at one of Aleppo’s last working hospitals, providing plenty of opportunities for all the air to be sucked out of the screening room as he holds the life of one small child after another in his hands. Al-Kateab narrates throughout, and the grief that undergirds her every sentence is less for her neighbors, because with so many of the randomly killed surrounding her, she would be unable to function if she mourned each loss. Rather, the grief is for the lost opportunity of the Arab Spring which kicked off when she was a college student and an active participant when it spread to Syria. Where once she planted gardens and laid down roots for a hopeful future, now she tunes out the constant thrum of Russian fighter jets and wonders where the next barrel bomb is going to indiscriminately land.

For anyone who’s watched a lot of documentaries, the smell of an artificial narrative can creep up at any moment. If the director captured hundreds of hours of footage, how do they decide what gets kept in a 90-minute final package? Is the easiest way to make cuts to find some throughline and include anything that supports it? Did perhaps their best scenes or interviews or shots have to be left out because they didn’t adhere to that throughline? As the person behind the camera on many documentaries, Kirsten Johnson is there to capture moments, but absent from the decision on what to include and what to omit. Her nonfiction masterpiece Cameraperson is assembled from those bits that were omitted, for whatever reason, from documentaries directed by the likes of Michael Moore, Laura Poitras, and Kirby Dick, among many others. Johnson doesn’t find a narrative link between scenes taking place in locations as different as a packed boxing match and a Bosnian family farm, but she locates a thematic thread in her life’s work and presents it to the viewer in empathic and affecting fashion as she simultaneously finds beauty and ugliness in the same images over and over again.

Documentaries are rarely served by the documentarians themselves appearing in front of the camera. Overheated navel-gazing ensues, or less irritatingly, they fail by being less interesting than the subject they’re filming. The exception to this is Agnes Varda, a distinctive and unique presence who is welcome to talk about herself onscreen for as long as she wants. In her beautiful Faces Places, the iconic French director teams up with youthful photographer JR for a trip through a lesser-seen France, far away from the streets of Paris. The unlikely duo bring joy wherever they go, both to the blue-collar inhabitants of the countryside and to the viewer.

|

Side PiecesRandom projects from the MMC Universe. Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed