|

As the fourth Star Wars film in four years, the troubled production that was Han Solo’s origin story is the sore thumb of the bunch. While each previous film has its detractors, some louder than others, Solo is the film whose critical dismissal and lackluster commercial haul was striking enough to push the giant ship of Disney away from continued annual returns to George Lucas’ universe. The energy of Solo itself is like a self-fulfilling prophecy, such that the actors and filmmakers may have anticipated how their work was going to be received, put their heads down, and made it to the final frame. From Ron Howard on down, no one seems creatively inspired or happy to be here, resulting in a film that has little impact after the credits roll.

0 Comments

The best kind of horror movies are about some kind of unspeakable impulse or thought embodied by demons or monsters. So much of David Cronenberg’s work is about a body revolting against its owner. The slasher movies of the 80’s enact some form of retributive morality on sexual freedom. Familial bonds aren’t spared from interrogation, whether in a classic like The Shining or the more contemporary Babadook. Ari Aster’s disconcerting debut Hereditary is in this last vein, stuffed with corrupted relationships to the point of bursting. It gives explicit voice to taboo feelings, especially about motherhood, as it moves between subgenres of horror in its different acts. Some of these transitions are more successful than others, but the total package is masterful in its evocation of earlier horror staples while also making its own contribution to the genre.

The documentary An Honest Liar posits that its subject, James Randi, has failed. Not at being a legendary escape artist and magician who is favorably compared to Houdini by peers, but at translating the performative philosophy of his craft into the public square. He describes magicians as being the most honest people in the world, because they are telling the truth even when they’re trying to trick their audience. Their feats are elaborate hoaxes and misdirections, and they never claim otherwise. Conversely, the most dishonest people are those that use the exact same tools as the magician and present themselves as being actually magical. Despite his elaborate public humiliations of these charlatans, they keep popping back up with a new scheme or excuse, impervious to the public’s weak critical thinking skills. Directors Justin Weinstein and Tyler Measom’s far-ranging film chronicles that Sisyphean fight, plus Randi’s professional and personal life as it goes through too-good-to-be-true twists and turns befitting a man who’s always kept people guessing.

Morgan Neville isn’t breaking new cinematic ground with Won’t You Be My Neighbor, a documentary about the life of children’s television host Fred Rogers. He’s not even as formally inventive as he is with his Oscar winner, 20 Feet From Stardom, in which he used memorable camera tricks to show how one backup singer can now do the work of several. This film is as straightforward and uncomplicated as its host, and it loses little power by being so. Sometimes, the choice of a documentarian’s subject is enough to make a film a dead ringer, and Won’t You Be My Neighbor has made that choice.

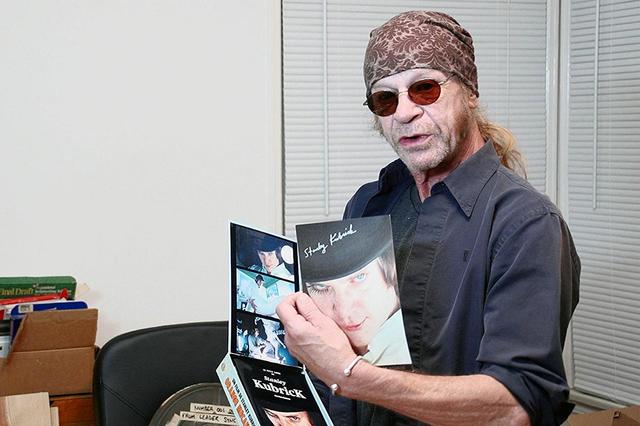

At the opening of the Stanley Kubrick exhibit at the LA County Museum of Art, 13 years after his 1999 death, the director’s personal assistant and guardian of his legacy, Leon Vitali, was not invited. Vitali is a living refutation of auteur theory, and there is no greater auteur than Stanley Kubrick. Perhaps having Vitali in attendance would’ve pulled focus from Kubrick. In Tony Zierra’s documentary about Vitali, it is the assistant who pulls focus from the auteur. Zierra’s Filmworker finds in Vitali the most dedicated below-the-line workhorse and makes a film dedicated to all those like him, men and women who ensure a film is completed in exchange for a blip in the end credits and the knowledge that even if no knows who they are, they too built that. This is a documentary that reframes how a person thinks about movies, and will cause this reviewer to think twice when he gives all the credit to the director.

The title of Matthew Nelson’s Who We Are Now refers to the irrevocable return to one’s earlier self after a life-changing event. The new person is still walking around in the old person’s body, but they can’t get their brain into the same place no matter how much they might want to or how much the people around them want to get back to normal. Reconciling that gap is shown to require a level of vulnerability that most people are incapable of, especially when desperation opens up the possibilities of easy exploitation. Nelson’s actors’ showcase is the ideal form of agitprop, one that resists speechifying and naked political statements for the lived experiences of those on the margins.

If a theme had to be forced onto the films that just happen to have been released in 2018, despair comes to mind. It’s been present in works ranging from arthouse indies like Eighth Grade and You Were Never Really Here to the big-budget spectacles of Avengers: Infinity War and Deadpool 2. Nowhere is despair more prevalent than in Paul Schrader’s haunting First Reformed, where all forms and all scales of dread are encapsulated by another of Schrader’s ‘god’s lonely men.’ Calling to mind the spare, religious-inflected introspection of mid-century masters like Robert Bresson, First Reformed is a bleak rebuke of hope and a dense treatise in search of it.

|

Side PiecesRandom projects from the MMC Universe. Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed