With John Travolta in a star-making role, Saturday Night Fever is part character study and part nature documentary. Travolta's Tony Manero is his pack's leader, and at every opportunity, he leads them onto the savannah of the disco to show off their manes and moves. Much more than the straightforward musical I always assumed it to be, Saturday Night Fever is both a snapshot of a subculture and a testament to how devoting oneself to a subculture can lead to isolation and ignorance.

Iconically introduced strutting down a Brooklyn street, Manero is king of all he surveys. John Badham's camera captures him from all different angles while the Bee Gees ring out on the soundtrack. Any conscious participant in American movie culture has seen pieces of this sequence, but it's actually Manero returning to a menial job at a paint store after running some errands. He still lives with his parents as the second son, overshadowed by the pride his mother and father feel for his priest older brother. Not only inferior in his parents' eyes, he also is belittled, despite his considerable talent on the dance floor. That distance between Manero's self-confidence and his actual station in life sustains Badham's film from start to finish.

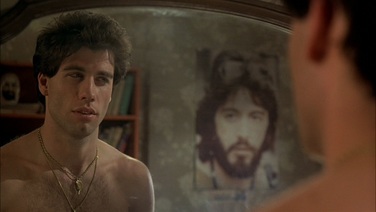

Manero might be in a dead-end job and live in an undermining home, but his self-confidence, derived from his high position in the disco community and among his crew, is justified. Badham intercuts scenes of Manero getting ready to go out with scenes at the disco, as if it's both calling to its favorite son and incomplete when he's not there. On the ride there, he dictates which cassettes his crew is going to listen to. Once inside, Manero and his crew stake out the high ground, taking in their surroundings and making plans before they mingle. Fawned over by the female clientele who plead to wipe the sweat off his brow, Manero will gladly dance with anyone that can keep up with him. The more homely patrons can get their moment in the spotlight with him if they've got the moves, while the more beautiful patrons will be summarily dismissed if they're sloppy. He's not dancing to get laid, like his friends, but because he loves to dance, and because he loves having all eyes on him while he's doing it.

Travolta and Tony Manero are inextricably linked, and it's as strong a pairing of character and actor as any. Travolta is exceptional in what's likely the best role of his career, moreso than Vincent Vega. His Tony is a font of charisma, even when the character's being a casual racist or homophobe. The viewer's willing to give him the benefit of the doubt, like he's doing it to fit in, as opposed to his crew who by turns are legitimately hateful. Away from the club and his crew and his parents, when he's allowed to be more vulnerable with his brother Frank (Martin Shakar) or love interest Stephanie (Karen Lynn Gorney), Travolta is able to communicate how torn Manero is between the joy he gets from dancing and the fear that there is a firm expiration date on his talent. That fear of being a has-been, stuck in the paint store without his sustaining outlet, makes it easy to sympathize with this alpha male despite his temporary command of his tiny community.

In another surprising facet, that community is honestly depicted by Badham as an often ugly and tribal place. On top of the casual intolerance mentioned earlier, Brooklyn is getting browner, demonstrated by the invasion of Latino music into the club and the hassling of Manero's crew by their Latino equivalents. Women are treated poorly, especially unofficial crew member Annette (Donna Pescow) who longs for Tony's affection. Badham gives everything a grubby feel, appropriate for the NYC of Taxi Driver and Serpico.

In this solidly working class and deeply religious environment, ambitions aren't running too high for Manero et al. It's easy to imagine what the next several years has in store for them if they stay as is. Stephanie is introduced as a contagion in this fairly-cloistered environment, sparking in Tony the possibility of something different. Lacking that kind of encouragement from his friends and parents, Travolta makes it appear as if leaving Brooklyn or going to school has legitimately never occurred to him. His desire to broaden his self-confidence on the dance floor to other aspects of his life is another deeply sympathetic impulse for a character otherwise trapped in his routine.

Alternatively raw and heightened, Saturday Night Fever was a pleasant surprise, an often-fun and affecting experience despite the innate corniness of the soundtrack and the film's broad legacy. Events do hinge on a dance contest, but Travolta infuses too much life into his work to not be enchanted by it. Badham isn't quite up to snuff when more action is required, as a rumble scene is a mis-ADR'd disaster, but Travolta more than picks up the slack. Disco might be dead, but Saturday Night Fever justly lives forever. B

RSS Feed

RSS Feed