The body selected to do the deed is Colin Tate (Christopher Abbott), an unimpressive man who’s managed to find himself engaged to Parse’s daughter Ava (Tuppence Middleton). Given an entry-level job at Parse’s company, Girder surmises that it will be easy for investigators to believe that the overlooked and underestimated Tate will strike against his high-handed father-in-law. Through a kidnapping scheme and the alternate-reality technology that allows for transferred consciousness, Vos assumes control of Tate but something’s off this time. At the moment of truth, Vos is unable to fully commit and a war for control of Tate’s body ensues between its true owner and Vos.

So much of Possessor is pulled out of David Cronenberg’s earlier work that is has to be commented on. Dual identities from Dead Ringers and History of Violence, loss of control from The Fly, extreme sexuality from Crash, tech as a virtual reality medium from eXistenZ, the base nature of the human body as a bag of meat from Scanners. It’s easy to imagine David making Possessor, but Brandon brings a precision that his father’s often messy films lacked. Some of that is the aesthetic drippiness that David’s creations like the Brundlefly or the fleshy compartments of Videodrome have, and some is the set dressing that the dusty basements and cluttered labs that David’s films tend to contain. Possessor, and Antiviral before it to a lesser extent, is clean and sterile, all the better to discomfit the viewer when the next horrific thing happens on a steel slab or an immaculate dining room. For all that the two directors share, it’s difficult to imagine David operating in Possessor’s world, a place where Brandon seems to be effortlessly comfortable and in control.

Control is also the name of the game in Possessor. The central plot mechanics war over who’s running Tate’s body, and the battle is brought to life in nightmare imagery and psychedelia, but the film goes deeper. How effective an assassin can Vos be if control of her own life is split between her work and her family, a family that she’s so disconnected from that she has to rehearse conversations with them before coming home? For both Vos and Tate, their work lives are surveilled constantly, with her projecting a stream of visualizations to Girder and him sat at a long bench with other drones, cataloguing everything in a customer’s house for some grim purpose of advertising optimization or something darker. There’s a constant fog that hangs over Possessor about suggestion and manipulation that prompts the viewer to consider why anyone does anything and at whose behest.

That fog is occasionally lifted by the senses-sharpening effect of sadistic violence. Anyone who’s observed a Twitter mob from a distance instantly recognizes the thematic link to Possessor, where one layer of remove allows a level of viciousness otherwise unthinkable. Vos is a savage beast when she’s attacking her prey, unleashing gouts of blood and gore that make the film practically unrecommendable to any but the most hardened horror fans. It’s all of a piece in how it relates to Possessor itself, especially when considering the set design and the surface propriety of these cutting-edge tech companies, but many scenes are difficult to watch. Compounding this further is the adrenaline rush stoked by Vos’ preferred mission termination, i.e. a self-inflicted shot to the brain. Her instability as an assassin is reflected in difficulty pulling the trigger, and this serves as a major front in the battle between Vos and Tate and between Vos and the woman in the prologue. Both Abbott and Graham are viscerally struggling to pull the trigger in a way that prompts the viewer to grip their armrests. Possessor is a film about mental invasion that also expertly strums the primal emotions of whoever is taking it in.

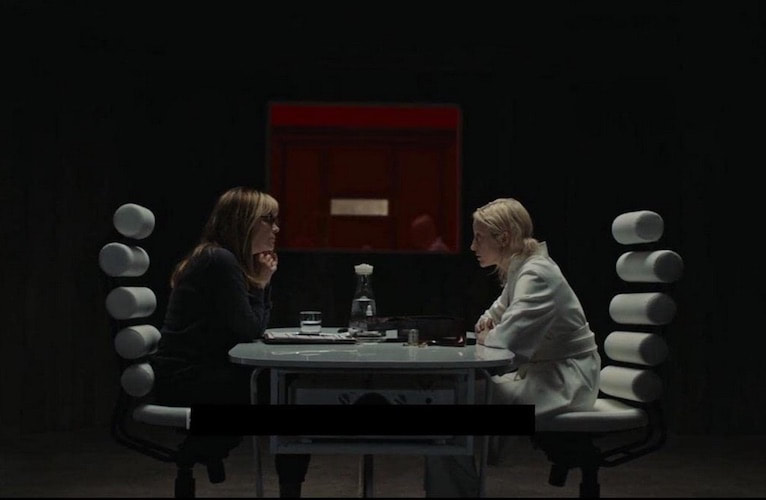

A film as relentlessly intense as this one asks a lot of its cast, and they do all requested and then some. Riseborough is a pallid ghost moving through the world, mysterious and purposefully hard to read. Her character is a good actor herself, but the discomfort of going through the motions is apparent on her body if not her face. Jason-Leigh gets her best role since Hateful Eight here as a cheerful and ostensibly sympathetic boss whose smiley post-op debriefs barely conceal a cold corporate ruthlessness. It’s Abbott, and to a lesser extent Graham thanks to her shorter screentime, who do the biggest acting. The aforementioned emotional tests, used as diagnostics by Vos, are both emotive exercises and deconstructions of meaningful reactions like tearing up or smiling with one’s eyes, here reduced to nothing more than electrical impulses. Both actors do them in single takes, only the first of several times that they’ll be asked to produce a response and wildly succeed. Abbott, to steal a line from Possessor, is a giant, nailing the loud terrifying moments and the tragic moments of desperation to get back to himself. There are distinct instances when he’s playing Tate, Vos-as-Tate, and some combination of the two. The degree of difficulty and the variation within Abbott’s performance make it impossible to take one’s eyes off him.

The deepest and darkest question Possessor is concerned with is about who can deal out violence and what that means for the individual. How does a person spend their work time dealing out death and go home to their families? Is it possible to simultaneously exist in a violent world and a domestic one, or is infection inevitable? That drawing of circles of worth and unworth around human life is the great conundrum of the species, and Brandon Cronenberg has presented it in a fearless and taboo fashion. Possessor is why horror and sci-fi films exist, to step outside of normal existence and ask why and what if, to interrogate the darkest and most unspeakable corners of the human psyche. There are few greater interrogators than those in the Cronenberg family. A

RSS Feed

RSS Feed