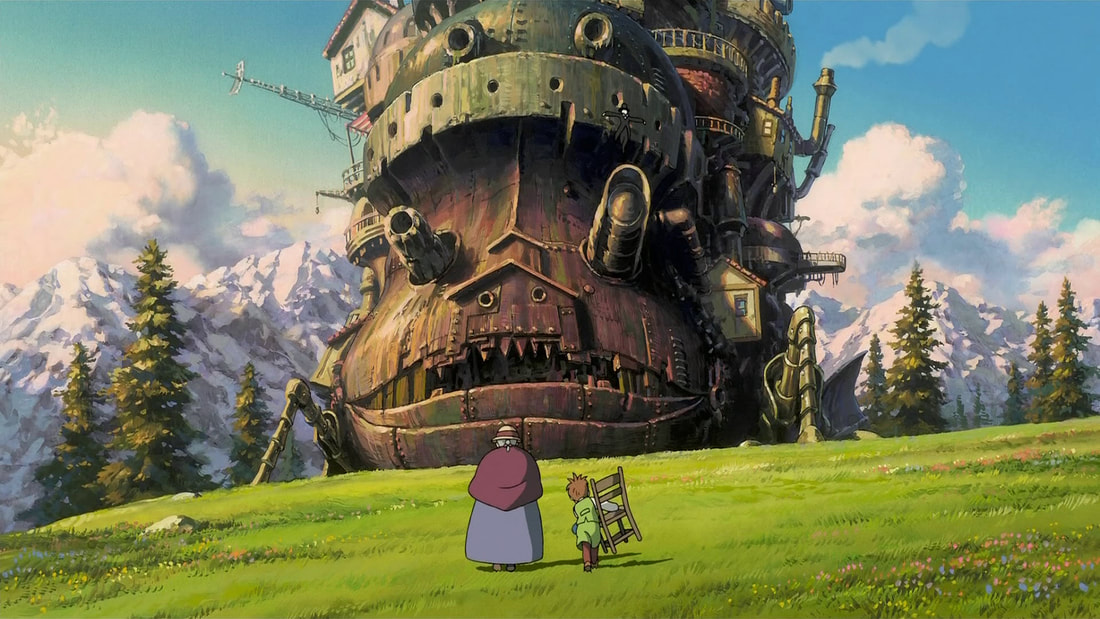

Once inside, Sophie takes in the castle's wonders, guiding the viewer through a magical world far away from the one she had previously known. There's a teleporter knob by the door, such that turning it will lead the exiter out of a shop in Sophie's city, a rival city, or wherever the castle is sitting. Markl has an appearance-altering mask that never ceases to be funny when he puts it on. The castle itself is a design miracle, anthropomorphized with a metal face and lolling tongue, bird legs that look far too weak to carry it, and dozens of chimneys and vents that blast smoke into the air. Howl is intermittently there, but when he is, his presence is like that of a surly teen. The interior is a cluttered mess, and when Howl's irritated, he goes into a comatose state and oozes goop everywhere. Miyazaki keeps throwing new amazements onto the screen, blending the practical and the fantastical with every frame.

Amidst the wonder that always exists in Miyazaki films, Howl's Moving Castle is grounded by its stalwart lineup of fantasy characters. Sophie leads the way, accompanied by JRPG staples like a little kid, a magical entity, and a cute animal in the form of an elderly dog that eventually joins the group. Much of the plot revolves around Calcifer, depicted as googly eyes and a mouth on a gout of flame, and for a character voiced by the oft-annoying Crystal, he provides a solid foundation and unobtrusive comic relief. Sophie is one of Miyazaki's better protagonists, functioning as more than the straight woman that things are happening to or around. Her transformation, from a young woman that feels invisible to an old woman who may as well be where society is concerned, is poetic enough to generate real pathos. Miyazaki repeatedly finds her staring out at breathtaking vistas from the castle's balcony, making her more contemplative than someone like Spirited Away's Chihiro but that doesn't make her passive. She has little patience for Howl's childish insecurities, forcing him into action and moving the film ever forward.

The anti-war aspect is where Howl's Moving Castle runs into trouble. The grander circumstances surrounding Sophie and Howl and the Witch of the Wastes find them as mere cogs in national politics, where their machinations are small potatoes against wars of indeterminate and possibly irrelevant causes. Being a powerful sorcerer, Howl is able to make a small impact on his own by sabotaging the forces of both armies, but each time he returns to his home, he's a little more animalistic and it takes a little longer to bring him back to normal. The war fills in the picture around the crew in the castle, but it doesn't serve much of a function beyond fleshing out Miyazaki's worldview. There's enough going on with the other characters to sustain the film on its own, and once these various interpersonal conflicts get resolved, the film betrays its feelings about the military backdrop by racing to the credits, pasting hasty resolutions in a move otherwise foreign to Studio Ghibli works.

With its giant metallic mouth, Howl's Moving Castle bites off more than it can chew. Miyazaki is on firmest ground with a story of arrested development and hastened infirmity. He would revisit his pacifist instincts with a more subtle attempt to interrogate man's warlike impulses in The Wind Rises. Here, it's a worthy cause executed inorganically. B

RSS Feed

RSS Feed