These are ordered from least to most spoilery, with links where available.

More Best of 2018:

Best Performances

Best Films

Bradley Cooper's modern update of the oft-remade A Star is Born sings as boldly and competently as its two leads for much of its runtime, but never as powerfully as Lady Gaga's Ally is coaxed to the stage by Bradley Cooper's Jack to debut Shallow, the song they wrote together during their first meeting. Both the film itself and Gaga hit their high points as Ally starts gingerly before belting out the ballad's refrain, relieved that she decided to take the mic and certain that she could do it all along. It's not surprising that Gaga can command a stage; it is surprising that she can so effectively convey a complete emotional arc in just under four minutes. It also doesn't hurt that the song's pretty good, too.

Saul Dibb’s adaptation of an English WWI play has the benefit of so many English works, in that there’s a never-ending supply of capable and charismatic actors ready and able to improve your film with their mere presence. Paul Bettany is one of these in Journey’s End, a veteran officer and a former headmaster as the war nears its bloody close. Selected along with Asa Butterfield’s green lieutenant Raleigh to go on a foolhardy mission into the German trenches, Bettany’s Osborne sense Raleigh’s nervousness and reverts to his peacetime role of being an ally to teen boys. He takes the last few minutes before they leave the relative safety of the officer’s quarters to distract Raleigh with talk of home, and though he needs a few tries, Osborne eventually gets a wistful smile out of the boy, taking him away from the meat grinder and back home for a mental respite before the whistle blows and they’re back in the mud. These two men are able to give each other an affecting gift before one heads out into a violent world for the first time and the other returns to it after years of pointless misery, years that haven’t yet robbed him of his kindness and decency.

Luca Guadagnino’s remake of Dario Argento’s Suspiria makes clear early on just how powerful the witches of the Tanz Dance Academy are. Where Argento’s sensuous original had a tenuous grasp of its story, Guadagnino ups the ante in the second of his three breathless and bravura dance sequences. Dakota Johnson’s Susie, a newcomer, is given the opportunity by troupe leader Madame Blanc (Tilda Swinton) to try out for the lead after previous lead Olga (Elena Fokina) storms out of the studio, furious with Blanc and the other matrons over the disappearance of a student. The camera follows Olga as she suddenly can’t stop crying and stumbles into a lonely studio, and then returns to Susie as she is touched by Blanc and then begins to dance. The violent routine of outthrust arms and jumps and spins is intercut with Olga being tossed around the studio, bones cracking and twisting with each of Susie’s movements. Guadagnino’s editing and sound effects sell Olga’s terror and, not unlike A Star is Born, the invigoration of Susie nailing something she’s trained her life for. That she takes such glee in the indirect brutalizing of a classmate is one of many sins the Tanz Academy will inflict on its members by the time it’s through with them.

Boots Riley’s everything-and-the-kitchen-sink debut saves most of its satirical edge for late-stage capitalism, but it cuts deep when it briefly rotates to think about music and culture. In Sorry to Bother You, Lakeith Stanfield’s Cash finds himself at a decadent party. Having achieved great success by making use of his ‘white voice’ on sales calls, he is reminded by the partygoers that while he can change his race over the phone, he is still black in person, and as such, everyone wants him to rap. Cash has no gift for this, but he realizes he can make the crowd roar in delight if he leads them in chants of ‘n-word shit’ over and over again. This deeply awkward and tragic scene confirms my suspicion that plenty of white people only like hip-hop because it gives them a way to say the n-word, but it also pushes Cash further into the depths of his Faustian bargain, trading away his conscience and his dignity for more money.

Hirokazu Koreeda has been making quiet and affecting family dramas for years. His latest, Shoplifters, received some of the highest acclaim of his career, and with scenes like this one, his reputation for honesty and affection is reinforced. The film focuses on a makeshift family of hustlers, though their actual bonds are tenuous. When they happen upon a young girl (Miyu Sasaki) hiding in an abandoned building and later listen to the girl’s parents cruelly yelling over her, they decide to keep her themselves. Their decision is ratified by the burns and bruises on the girl, and while she bonds most with the family’s tween boy (Kairi Jo), it’s matriarch Nobuyo (Sakura Ando) who is most protective towards the girl. In one of the most affecting scenes of Koreeda’s long track record of tearjerkers, Nobuyo and the girl, who they christen as Lin, compare scars and discuss how hugs are how little kids are supposed to be touched by the adults who love them. The scene, watched by the rest of the family, ends with Lin wiping a tear off of Nobuyo’s cheek, either a brilliant improv on the part of an intuitive young actor or a crushing exclamation point from one of cinema’s best directors.

Lee Chang-dong’s atmospheric thriller Burning starts as a love triangle before becoming something wholly different. The turning point comes halfway through the film when the three main characters have all been credibly established. At the rural home of poor aspiring writer Jong-su (Yoo Ah-in), his crush object Hae-mi (Jeon Jong-seo) and her wealthy and mysterious companion Ben (Steven Yuen) are visiting. Ben offers everyone some weed, which the dreamy and ethereal Hae-mi partakes in and then, entranced by the setting sun, performs a hypnotic dance, not for the two men but for herself. Having earlier referenced the idea of the Big Hunger for grand meaning she learned about while on a trip in Kenya, she embodies it in a long, twilight scene, her body swallowed up by the darkening sky. In a lesser film, this is eccentric manic pixie dream girl behavior, but with a master like Lee, it’s earnest and guileless and wholly lost on her two companions, neither of whom appreciate this naked moment of truth and beauty.

The rock-opera drug trip that is Mandy doses its characters with so many hallucinogens that the feeling bleeds out of the screen and disorients the viewer. Much of what takes place can be doubted and questioned as the LSD-fueled ravings of a mad man, but Panos Cosmatos’ film is crystal clear in its best moments. Margaret Atwood’s famous saying about men fearing women will laugh at them while women fear men will kill them is brought to woozy life by Andrea Riseborough’s titular character. Captured by the sex cult of Jeremiah Sand (Linus Roache) and slated to join his harem, Mandy is dosed with some kind of insect venom and brought before the man, a discount Charlie Manson with a robe and penchant for grandiosity. He raves about how great he is and stands naked in perceived glory before her, giving her the chance to join him willingly. And she laughs at him. Not a nervous chuckle but a full-throated guffaw followed by forceful, sustained, mocking, stunted bellows, majestic assertions that he won’t intimidate her and she won’t submit to his pathetic attempt to dress up his need for praise as anything other than rank uselessness. Cosmatos distorts the score and Riseborough’s angular face, giving the effect that she’s some otherworldly being, coming from the underworld to drag this laughable man’s pride back down below with her.

First Man does indeed fulfill its title and send Neil Armstrong (Ryan Gosling) to the moon. In Damien Chazelle’s mind-blowing epic, he shirks the cosmic awe of something like 2001 or Contact. The landing itself, a difficult and clanky feat of engineering seemingly held together with stubbornness and adhesive, has never felt so utilitarian. The lunar surface is barren and empty, and Armstrong’s taciturn nature throughout the rest of the film doesn’t suddenly lift in a moment of accomplishment and joy. Instead, placing the viewer in as stripped-down a version of this achievement as possible forces them to really confront why this was worth it, which for me, magnified the value. As this realization is coursing over the viewer, Armstrong is having a moment of catharsis over his long-dead daughter, shown dying from cancer at the film’s beginning. He finds an empty crater, and as alone as few other men have ever been, he tosses a locket of hers in. First Man blends the historical and the personal in a tremendously effective way, and scenes like this ensure its place amongst its space exploration predecessors.

The critical horror favorite of the year, Ari Aster’s Hereditary earns its accolades with unbearable levels of emotional intensity. This is most true after a first act twist that leaves the Graham family’s odd daughter Charlie (Milly Shapiro) a headless corpse in their teen son Peter’s (Alex Wolff) backseat. After mother Annie’s (Toni Collette) initial piercing burst of grief, things in the house settle into cold recrimination and aloofness, until a family dinner. Peter wants to break the silence, and prods Annie to talk with him about how Charlie died, prodding that sends Annie into a berserk rage of regret and guilt and accusation. Collette has several monologues in the film, but this one pushes the viewer back in their seats as she says exactly what she’s thinking to her son while husband Steve (Gabriel Byrne) impotently tries to stop her. Hereditary is at its very best as a twisted family drama, just as horrific in how brutal the Grahams are to each other as when it takes a sharp turn into bumps in the night.

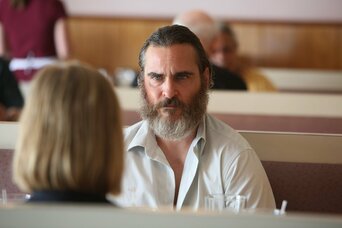

Joaquin Phoenix’s Joe has spent the entirety of You Were Never Really Here in small spasms of self-harm, masochistic sense memories that remind him the many acts of violence he’s witnessed or been a part of. Unable to get free of all this baggage, he’s biding time until his mother (Judith Roberts) dies and he can follow her to the grave, finally free of all that’s been plaguing him. When she’s killed by hitmen after him following a job gone bad, Joe contemplates suicide but changes his mind to rescue the focus of the job, a girl named Nina (Ekaterina Samsonov). He haphazardly finds her, though she seems to be able to take care of herself, and at the end of Lynne Ramsay’s bleak masterpiece, the mismatched pair sits down in a diner. When Nina excuses herself, Joe wordlessly whips out his pistol and shoots himself under the chin, spraying blood and brain all over the diner and its patrons. This would be a wholly believable place for Ramsay to end her film, but the diners keep talking, unmoved by what just happened and confirming Joe’s film-long desire to not be seen and not affect anyone beyond who he must. Nina returns and shakes him awake from his imaginary suicide, and the two leave the diner. As the story of a broken man losing his reason for living and maybe finding a new one, You Were Never Really Here finds the barest glimmer of hope as the credits roll, and those diners keep on talking, oblivious to the revelation that is exiting the booth behind him.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed