In Antiviral, the apple doesn’t fall from the tree. Brandon Cronenberg, son of body horror master David, is just as enamored with decay and mutation as his father. Where Papa Cronenberg employed nightmares of horrific tumors and growths, Cronenberg Junior counters with cloned human meat and copious bodily fluids. The similarities go beyond the grotesqueries on display. Both also like to overlay their images on top of a satirical base. Antiviral is filled with the can’t-look-away, but it’s also concerned with the culture’s obsession with celebrity. Its tabloid knob might be turned to 11, but a lock of Bieber’s hair can go for thousands of dollars and an episode of the Big Bang Theory revolved around Leonard Nimoy’s dirty handkerchief. Antiviral presupposes a science-fiction future, but one with plenty of grains of truth.

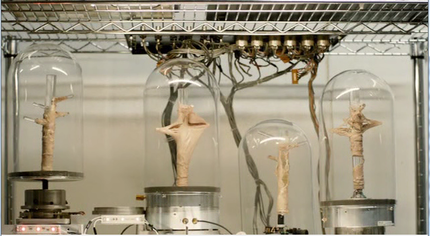

Antiviral’s central conceit is that the bodily products of celebrities have become a giant market. One facet of this is butcher shops, where cloned celebrity muscle cells are assembled into patties in the backroom and sold for consumption. For the squeamish, pliable software programs are also prevalent, where the user can tell the computerized image of a celebrity to do anything they want him/her to do. The most invasive new industry is the collection of pathogens that have infected celebrities, which are then injected into civilians for a hefty fee. The pathogens are rendered incommunicable to ensure they can’t be passed on, but the point is to be able to proudly display the herpes sores that once adorned one’s favorite actress.

It’s in this industry that the protagonist finds himself. Syd March (Caleb Landry Jones) works as a salesman for the Lucas Clinic, which has several in-demand celebrities on retainer. Lucas gets exclusive rights to their colds, flus, and rashes. March is revealed as not only an employee, but also a client. He is able to smuggle samples of the Lucas’s various diseases out of his workplace by infecting himself. At home, using stolen equipment, he is then able to crack the genetic encryption that prevents the disease from infecting anyone else. Now in possession of communicable diseases that once ravaged famous bodies, he sells samples to underground dealers. When tasked by Lucas with personally collecting a heretofore unknown disease from the particularly in-demand Hannah Geist (Sarah Gadon), he can’t resist injecting some of her blood into himself. When the news breaks that she has died, March realizes that not only has he infected himself with a fatal disease, but he has also put a target on his back. There is a significant demand to know what Geist felt like before she died, and March is now the key to that knowledge.

True to expectations, Cronenberg is repeatedly showing crumbling bodies and the general grossness of anatomy. March is often collecting his own blood, and the entire process is captured. When afflicted with respiratory diseases, March sticks a swab deep, deep into his nose to get a sample. The sound of chopping up cloned muscle masses into single servings is captured in all its wet, sucking glory. March’s fever dreams are predictably messed up, as his body sprouts cables and his skin grows over his mouth. Cronenberg loves himself some red in the frame, but he also loves framing it against white backgrounds. The labs and reception halls of Lucas are pristine, blinding whit, as is the opening shot, which is simply a sickly March standing against a white billboard. That juxtaposition of the film’s messy and grimy actions against what feels like a sterile setting adds to the already-significant discomfort.

The dystopian satire on display is less effective than the body horror. Making fun of celebrity culture is a big, easy target. Its current incarnation is already so self-evidently absurd, that escalation is barely necessary. Despite Cronenberg’s easy choice of topic, he includes a few touches that are appreciated against the broad metaphor of the premise. It’s never stated what the coveted celebrities like Geist actually do: they are simply famous. As the world of the film is obsessed with tangible experiences, the intangible products (music, film, art) that might make a celebrity worthy of admiration are irrelevant. Cronenberg also designates a couple characters as sages that are allowed to pontificate on Antiviral’s society. Memorably, a doctor played by Terrence Stamp derides organized religion in one breath and shows off his celebrity skin grafts in the next. Everyone parrots the company line in Antiviral. No truth-tellers are allowed to puncture the atmosphere.

Antiviral is a strong first feature from Brandon Cronenberg. He manufactures multiple striking images, and he gets a chilling depiction of mental and physical deterioration out of Jones. David Cronenberg has moved away from the body horror of his early career, exchanging larval abortions for acidic Hollywood satire. Though one of the genre’s great proponents is paying it less tribute, there’s another potential master of the icky ready to take his place. B-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed